In Vivo LNP-Engineered Cytokine-Armored CAR Cells For Solid Tumors

By Parv Barot

The clinical success of autologous CAR-T cell therapies, such as Kymriah and Yescarta, has been hailed as a "penicillin moment" for cancer. Yet, the operational reality of these therapies is often described as a logistical nightmare and uncertain. The standard "vein-to-vein" cycle — harvesting T cells via leukapheresis, shipping them to a centralized facility for viral transduction and expansion, and returning them for infusion — typically spans three to four weeks. For patients with rapidly progressing disease, this delay can be a ticking time bomb scenario. Furthermore, the biological quality of the final product is often compromised; T cells harvested from heavily pre-treated patients frequently exhibit signs of exhaustion before they are even engineered, leading to manufacturing failures or poor persistence post-infusion.

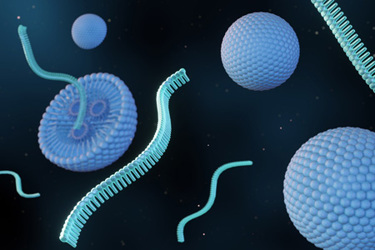

The field is now pivoting toward a radical conceptual shift: moving the manufacturing facility from the laboratory into the patient's own body. In vivo programming represents the transition from cell therapy to gene therapy, where the therapeutic agent is not the cell itself, but a nanoparticulate vehicle delivering genetic instructions. By injecting lipid-based nanoparticles (LNPs) encapsulating mRNA and encoding the CAR directly into the bloodstream, we can effectively reprogram the patient's own immune cells in situ. This "off-the-shelf" approach eliminates the need for lymphodepleting chemotherapy and drastically reduces the cost and time to treatment. However, simply generating CAR-T cells in vivo is insufficient for the conquest of solid tumors. To breach the physical and metabolic fortress of a glioblastoma (GBM) or pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, these cells must be upgraded with "armor" — a payload of pro-inflammatory cytokines that remodels the local environment to favor tumor elimination.

LNP Technology For Immune Cell Targeting

The success of in vivo engineering hinges on the delivery vehicle. Standard LNPs, such as those used in COVID-19 vaccines, rely on passive targeting. When injected intravenously, they adsorb Apolipoprotein E (ApoE) from the plasma, which directs them to low-density lipoprotein (LDL) receptors on hepatocytes, resulting in massive accumulation in the liver. While excellent for treating liver diseases, this "liver sponge" effect is detrimental when the goal is to transfect circulating T cells or natural killer (NK) cells.

To overcome this, next-generation LNPs employ active targeting strategies. By conjugating monoclonal antibodies or antibody fragments to the surface of the LNP, researchers can steer these vehicles toward specific immune subsets. For T cells, antibodies against CD3, CD4, or CD8 allow for precise docking and internalization. Companies like Capstan Therapeutics (AbbVie) have pioneered the use of CD8-targeted LNPs to specifically engineer cytotoxic T cells while sparing regulatory T cells, thereby enhancing the safety profile. Similarly, for NK cells, targeting the natural cytotoxicity receptor NKp46 has proven effective in delivering mRNA payloads to these notoriously hard-to-transfect innate effectors.

Once the LNP binds its target, the payload, messenger RNA (mRNA) or circular RNA (oRNA), is released into the cytoplasm. This transient nature of mRNA expression is a critical safety feature of in vivo immunotherapy. Unlike viral vectors that permanently integrate into the genome, posing risks of insertional mutagenesis and long-term toxicity, mRNA-derived CARs are expressed only for a few days. This "hit-and-run" kinetics reduces the risk of persistent side effects like uncontrolled cytokine release syndrome (CRS) or on-target/off-tumor toxicity, allowing clinicians to control the "dose" of the therapy simply by stopping the LNP infusions.

Armored CARs And The Cytokine Trinity (IL-12, IL-15, IL-18)

For solid tumors, the expression of a CAR alone is often a futile gesture. The tumor microenvironment (TME) is an immunosuppressive landscape characterized by hypoxia, nutrient deprivation, and the presence of suppressor cells. To survive and function in this hostile territory, in vivo engineered cells are "armored" to co-express a trinity of potent cytokines: IL-12, IL-15, and IL-18.

Interleukin-12 (IL-12) acts as the "inflamer." It is crucial for remodeling the TME, shifting it from a "cold" immunosuppressive state to a "hot" pro-inflammatory one. IL-12 stimulates the secretion of Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) and recruits innate immune cells, such as macrophages and NK cells, to the tumor site. However, systemic IL-12 is highly toxic. In vivo CAR designs mitigate this by engineering the cells to secrete IL-12 locally at the immunological synapse or by using inducible promoters that trigger secretion only upon CAR antigen binding. This synaptic delivery ensures that the cytokine remodels the tumor stroma without triggering a systemic cytokine storm.

Interleukin-15 (IL-15) serves as the "sustainer." It is indispensable for the persistence and survival of T and NK cells. In the absence of IL-15, CAR T cells in the TME rapidly succumb to apoptosis. Armoring CARs with membrane-bound IL-15 provides an autocrine survival signal that maintains the effector pool and promotes the formation of stem cell-like memory T cells (Tscm), which are critical for preventing tumor relapse.

Interleukin-18 (IL-18) functions as the "potentiator." Recent data suggests that IL-18 is a master regulator of metabolic reprogramming in effector cells. It enhances oxidative phosphorylation and glutaminolysis, providing the metabolic fuel necessary for T cells to function in the glucose-deprived environment of a solid tumor. Furthermore, IL-18 synergizes with IL-12 to induce massive IFN-γ production, enhancing tumor cell killing without the severe toxicity associated with high-dose systemic IL-2 therapy.

Solid Tumors Vs. Autoimmune Diseases

The application of LNP-driven, cytokine-armored CARs is reshaping the battlefield in both oncology and autoimmunity. In solid tumors, the primary challenge is physical and metabolic exclusion. For instance, in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, a dense stroma generated by cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) blocks T cell entry. In vivo strategies targeting the fibroblast activation protein (FAP) on CAFs can dissolve this physical barrier. Simultaneously, the cytokine armor allows the infiltrating cells to survive the hypoxic core. In GBM, the blood–brain barrier (BBB) poses an additional hurdle. Here, the combination of focused ultrasound (FUS) with microbubbles has been shown to transiently open the BBB, allowing intravenously administered LNPs to penetrate the brain parenchyma and transfect immune cells within the central nervous system.

Conversely, in the realm of autoimmune diseases, the goal is not permanent surveillance but a tactical reset. Diseases like systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and multiple sclerosis (MS) are driven by autoreactive B cells. The in vivo approach is uniquely suited here. By delivering anti-CD19 or anti-BCMA CAR mRNA via LNPs, therapy can induce a deep, transient depletion of B cells. Unlike viral CAR-T therapy, which risks permanent B cell aplasia and lifelong immunoglobulin replacement, the transient nature of mRNA allows the CAR T cells to disappear after the job is done. This hit-and-run depletion eliminates the pathogenic B cell clones, allowing the bone marrow to repopulate the compartment with healthy, naïve B cells, which will effectively reboot the immune system.

Future Perspectives And Challenges

As we advance toward the clinical translation of this technology, several hurdles remain. The most significant concern is off-target transfection. If the LNP payload is inadvertently delivered to a vital organ (for example, if a lung epithelial cell expresses the CAR), this will result in on-target, off-tumor toxicity, which could be catastrophic. To mitigate this, researchers are incorporating microRNA (miRNA) target sites (e.g., miR-122) into the mRNA payload, with silence expression in the liver or other non-immune tissues, ensuring the CAR is only expressed in hematopoietic cells.

Dosing control also represents a paradigm shift. Unlike ex vivo therapy, where a defined number of cells are infused, in vivo therapy resembles a traditional drug regimen. Clinicians must determine the optimal concentration of LNPs to achieve a therapeutic dose of CAR T cells inside the body. This titratability, however, is also an advantage, allowing for repeat dosing to maintain pressure on the tumor or to manage toxicity by withholding doses.

Ultimately, the transition to LNP-driven in vivo immunotherapy promises to democratize access to advanced cancer care. It envisions a future where CAR-T therapy is not a complex, boutique procedure limited to specialized academic centers, but an off-the-shelf pharmaceutical product available at any hospital pharmacy. By combining the precision of genetic engineering with the scalability of nanomedicine, we are moving closer to the holy grail: a potent, accessible, and adaptable cure for the most challenging human diseases.

About The Author

Parv Barot, MS, has contributed to the development of next-generation CAR-T and NK cell-based immunotherapies targeting solid tumors and hematological malignancies at Angeles Therapeutics. He is currently engaged in oncology and autoimmune disease research at Novasenta, where he conducts mechanism-of-action and proof-of-concept studies in support of antibody discovery programs, working closely with molecular biology and assay development teams.

Parv Barot, MS, has contributed to the development of next-generation CAR-T and NK cell-based immunotherapies targeting solid tumors and hematological malignancies at Angeles Therapeutics. He is currently engaged in oncology and autoimmune disease research at Novasenta, where he conducts mechanism-of-action and proof-of-concept studies in support of antibody discovery programs, working closely with molecular biology and assay development teams.