From Cyclization To The Clinic: The Rising Era Of Cyclic Peptide Therapeutics

By Gianni Cavallo, Ph.D.

The pharmaceutical industry is currently experiencing a golden era for cyclic peptide therapeutics. As of June 2024, 66 peptide-based drugs have been approved worldwide, with many additional candidates in late-stage clinical development or under regulatory review.1,2 What is driving this rapid expansion? Cyclic peptides have emerged as attractive drug candidates for traditionally “undruggable” targets, particularly protein–protein interactions (PPIs).3,4 They can bind with high affinity to a wide range of proteins, while also exhibiting oral bioavailability and cellular permeability.5 These features have significantly broadened the therapeutic scope of peptide-based drugs and have driven growing investment and development efforts across the field.

Why Cyclize Peptides?

Linear peptides offer several advantages, including higher target specificity, extended half-lives, and generally lower toxicity and immunogenicity relative to many other therapeutic molecules.6 A good example is semaglutide, the first oral glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1RA), which has demonstrated marked clinical success in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus and weight loss.6

Despite these strengths, many linear peptides exhibit poor metabolic stability due to rapid proteolytic degradation and often need subcutaneous or intravenous administration to achieve adequate bioavailability.6 These limitations can negatively impact patient compliance and restrict clinical utility.

Macrocyclization addresses several of these challenges by inducing conformational rigidification, which limits protease accessibility and shields terminal residues from exopeptidase cleavage, thereby improving metabolic stability and pharmacokinetics.7–9 Moreover, macrocyclization increases backbone rigidity, reducing the entropic penalty upon binding and stabilizing bioactive conformations.2,7 This leads to therapeutics with high metabolic stability, improved target affinity, and, in some cases, increased oral bioavailability.8,9

Furthermore, the incorporation of non-canonical amino acids, together with advances in cyclization chemistry, has enabled substantial expansion of the accessible chemical space.6,10 This versatility allows cyclic peptides to bridge key gaps between small molecules and biologics.11

An Overview Of Current Cyclization Strategies

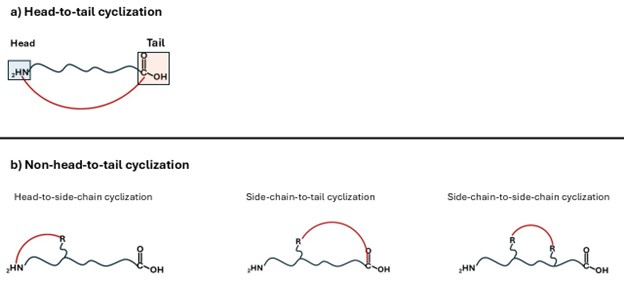

The most established macrocyclization approach is head-to-tail cyclization, achieved through condensation of the terminal amino and carboxyl groups (Fig.1.a).12 However, macrocyclization also can be performed at alternative positions along the backbone, resulting in non-head-to-tail cyclizations (Fig.1.b).13 These include:

- Head-to-side-chain cyclization: bond formation between the N-terminal amino group and a side-chain functional group.

- Side-chain-to-tail cyclization: bond formation between a side-chain functional group and the C-terminal carboxyl group.

- Side-chain-to-side-chain cyclization: bond formation between two side chains.

Fig.1: Strategies for the cyclization of linear peptides

A wide range of chemical reactions can be used to achieve these non-head-to-tail architectures.2,13–15 These include biorthogonal reactions such as azide–alkyne cycloadditions (CuAAC), as well as non-biorthogonal approaches, including disulfide bond formation — via orthogonal disulfide pairing or disulfide stapling — ring-closing metathesis, and other related reactions.2,13–15 The chemistry employed to generate these architectures influences the resulting three-dimensional structure and, consequently, the bioactivity and the pharmacokinetic properties of cyclic peptides, including bioavailability and half-life.16

Peptides also can be engineered to undergo successive macrocyclization, generating polycyclic peptides.17 These can display antibody-like affinity and selectivity, while avoiding many of the size, manufacturing, and delivery challenges associated with monoclonal antibodies.7,17 This is due to their increased conformational restriction, which enhances binding affinity and reduces entropic penalties upon target engagement.12,17 These rigid molecules interact with extended protein surfaces, permitting binding at active sites and adjacent regions.7,17

In addition, polycyclization has been shown to enhance membrane permeability and oral exposure — properties that are increasingly prioritized in peptide drug development.12

At the same time, the synthesis of such architectures remains challenging, requiring a well-designed synthetic strategy that ensures precise reaction site selectivity and broad functional group tolerance.12,17 These synthetic challenges can have a direct impact on downstream development timelines and manufacturability.

Macrocyclic Peptides In Practice: Lessons from Drug Development

Several macrocyclic peptide therapeutics have either reached the market or advanced into late-stage clinical development, including Zilucoplan, Gadopiclenol, MK-0616 (enlicitide decanoate), and Icotrokinra.18,19 The following section highlights Zilucoplan for its clinical impact and MK-0616 as a leading example of an orally administered macrocyclic peptide, briefly describing their development.

Zilucoplan is a once-daily, subcutaneously administered peptide inhibitor of complement component 5 (C5) approved in 2023 for the treatment of generalized myasthenia gravis (gMG).20 By inhibiting C5 activation, Zilucoplan prevents the activation of the terminal complement cascade, thereby stopping the formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC, C5b-9), which is responsible for cell lysis and tissue damage.21 Compared with long-acting monoclonal antibodies, Zilucoplan offers more flexible dosing, which may be advantageous for individualized disease management.22

Zilucoplan was developed from macrocyclic peptide leads identified using an mRNA display platform to screen for C5 inhibitors, followed by systematic optimization to produce a clinical candidate.23 The head-to-side-chain cyclization of the linear peptide was performed in solution via formation of a lactam bridge between the side chains of Z-lysine and Z6-aspartic acid residues.24 The molecule exhibits high binding affinity, cell permeability, metabolic stability, and favorable overall pharmacokinetic properties, underscoring the central role of cyclization in its clinical success.24

Another notable example is MK-0616, a macrocyclic peptide targeting PCSK9 that is currently in Phase 3 clinical development as the first orally administered agent in this class.25,26 By disrupting PCSK9 binding to the LDL receptor, MK-0616 produces clinically meaningful reductions in plasma LDL-cholesterol levels.26,27

MK-0616 was derived from macrocyclic peptide leads identified through mRNA display screening and subsequently optimized using structure-based drug design.25 Several chemical modifications were introduced to address key limitations of the lead scaffold, including susceptibility to oxidative degradation, suboptimal solubility, and low membrane permeability.28 To enhance intestinal absorption, MK-0616 was co-formulated with a permeation enhancer that increases paracellular transport by facilitating size-limited passage through junctions of intestinal epithelial cells.28 As a result, the molecule exhibits high in vitro binding affinity for PCSK9 and achieves oral bioavailability of approximately 2%, which is notable for a peptide therapeutic.28

From a synthetic perspective, MK-0616 is obtained via a multistep macrocyclization strategy.29 An initial head-to-tail cyclization is performed in solution, followed by a second macrocyclization performed through ring-closing metathesis between two side chains and subsequent reduction of the resulting double bond.29 This polycyclic architecture contributes to antibody-like affinity and high selectivity for PCSK9, positioning MK-0616 as a differentiated therapeutic option, particularly for patients who are unable or unwilling to use injectable therapies.27,28

Conclusions

Macrocyclic peptides are no longer a niche technology but a growing field within drug discovery. They overcome many of the limitations that historically constrained linear peptide therapeutics by stabilizing bioactive conformations and improving metabolic stability, target affinity, and pharmacokinetic profiles.12,17

Advances in cyclization chemistry, together with expanded use of non-canonical amino acids, have substantially broadened the accessible chemical space.6,10 Combined with modern discovery platforms, such as mRNA display and structure-based drug design, these tools enable the synthesis of potent and selective drug candidates against challenging targets.23,28

Supported by sustained industrial and academic investment, together with progress in scalable synthesis, process development, and manufacturability, macrocyclic peptides are bridging the gap between small molecules and biologics. Whether this golden era represents just a temporary momentum or will translate into sustained clinical and commercial success across therapeutic areas remains an open question. Nevertheless, current trends indicate a growing role for macrocyclic peptides in addressing unmet medical needs.

References

- Cyclic Peptides: FDA-Approved Drugs and Their Oral Bioavailability and Metabolic Stability Tactics.

- Costa, L., Sousa, E., and Fernandes, C. (2023). Cyclic Peptides in Pipeline: What Future for These Great Molecules? Pharmaceuticals 16, 996. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16070996.

- Jones, D., Carbone, M., Invernizzi, P., Little, N., Nevens, F., Swain, M.G., Wiesel, P., and Levy, C. (2023). Impact of setanaxib on quality of life outcomes in primary biliary cholangitis in a Phase 2 randomized controlled trial. Hepatol. Commun. 7, e0057. https://doi.org/10.1097/HC9.0000000000000057.

- Kingwell, K. (2023). Macrocycle drugs serve up new opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 22, 771–773. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41573-023-00152-3.

- You, S., McIntyre, G., and Passioura, T. (2024). The coming of age of cyclic peptide drugs: an update on discovery technologies. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 19, 961–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/17460441.2024.2367024.

- Xiao, W., Jiang, W., Chen, Z., Huang, Y., Mao, J., Zheng, W., Hu, Y., and Shi, J. (2025). Advance in peptide-based drug development: delivery platforms, therapeutics and vaccines. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 10, 74. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-024-02107-5.

- Buckton, L.K., Rahimi, M.N., and McAlpine, S.R. (2021). Cyclic Peptides as Drugs for Intracellular Targets: The Next Frontier in Peptide Therapeutic Development. Chem. – Eur. J. 27, 1487–1513. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.201905385.

- Montgomery, J.E., Donnelly, J.A., Fanning, S.W., Speltz, T.E., Shangguan, X., Coukos, J.S., Greene, G.L., and Moellering, R.E. (2019). Versatile Peptide Macrocyclization with Diels–Alder Cycloadditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 16374–16381. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.9b07578.

- Bozovičar, K., and Bratkovič, T. (2021). Small and Simple, yet Sturdy: Conformationally Constrained Peptides with Remarkable Properties. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 22, 1611. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22041611.

- Wang, L., Wang, N., Zhang, W., Cheng, X., Yan, Z., Shao, G., Wang, X., Wang, R., and Fu, C. (2022). Therapeutic peptides: current applications and future directions. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 7, 48. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-00904-4.

- Dougherty, P.G., Sahni, A., and Pei, D. (2019). Understanding Cell Penetration of Cyclic Peptides. Chem. Rev. 119, 10241–10287. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00008.

- Fang, P., Pang, W.-K., Xuan, S., Chan, W.-L., and Cham-Fai Leung, K. (2024). Recent advances in peptide macrocyclization strategies. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 11725–11771. https://doi.org/10.1039/D3CS01066J.

- Bechtler, C., and Lamers, C. Macrocyclization strategies for cyclic peptides and peptidomimetics. RSC Med. Chem. 12, 1325–1351. https://doi.org/10.1039/d1md00083g.

- Reichwein, J.F., Versluis, C., and Liskamp, R.M.J. (2000). Synthesis of Cyclic Peptides by Ring-Closing Metathesis. J. Org. Chem. 65, 6187–6195. https://doi.org/10.1021/jo000759t.

- Hayes, H.C., Luk, L.Y.P., and Tsai, Y.-H. (2021). Approaches for peptide and protein cyclisation. Org. Biomol. Chem. 19, 3983–4001. https://doi.org/10.1039/D1OB00411E.

- Darling, W.T.P., Wieske, L.H.E., Cook, D.T., Aliev, A.E., Caron, L., Humphrys, E.J., Figueiredo, A.M., Hansen, D.F., Erdélyi, M., and Tabor, A.B. (2024). The Influence of Disulfide, Thioacetal and Lanthionine-Bridges on the Conformation of a Macrocyclic Peptide. Chem. – Eur. J. 30, e202401654. https://doi.org/10.1002/chem.202401654.

- Feng, D., Liu, L., Shi, Y., Du, P., Xu, S., Zhu, Z., Xu, J., and Yao, H. (2023). Current development of bicyclic peptides. Chin. Chem. Lett. 34, 108026. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cclet.2022.108026.

- Du, Y., Semghouli, A., Wang, Q., Mei, H., Kiss, L., Baecker, D., Soloshonok, V.A., and Han, J. (2025). FDA-approved drugs featuring macrocycles or medium-sized rings. Arch. Pharm. (Weinheim) 358, e2400890. https://doi.org/10.1002/ardp.202400890.

- Gooderham, M., Lain, E., Bissonnette, R., Huang, Y.-H., Lynde, C.W., Hoffmann, M., Song, E.J., Weirich, O., Ceitlin, R.H.G., Rubens, J.H., et al. (2025). Targeted Oral Peptide Icotrokinra for Psoriasis Involving High-Impact Sites. NEJM Evid. 4, EVIDoa2500155. https://doi.org/10.1056/EVIDoa2500155.

- Shirley, M. (2024). Zilucoplan: First Approval. Drugs 84, 99–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-023-01977-3.

- Tang, G.-Q., Tang, Y., Dhamnaskar, K., Hoarty, M.D., Vyasamneni, R., Vadysirisack, D.D., Ma, Z., Zhu, N., Wang, J.-G., Bu, C., et al. (2023). Zilucoplan, a macrocyclic peptide inhibitor of human complement component 5, uses a dual mode of action to prevent terminal complement pathway activation. Front. Immunol. 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1213920.

- Versino, F., and Fattizzo, B. (2024). Complement inhibition in paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria: From biology to therapy. Int. J. Lab. Hematol. 46, 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijlh.14281.

- Ye, P., Hammer, R.P., Wang, Z., Dhamnaskar, K., Hoarty, M., Ma, Z., Tang, G.-Q., DeMarco, S.J., and Ricardo, A. (2025). Discovery of Zilucoplan: A Complement C5 Inhibitor for Treatment of Anti-Acetylcholine Receptor (AChR) Antibody-Positive Generalized Myasthenia Gravis (gMG). J. Med. Chem. 68, 25772–25782. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5c02537.

- Costa, L., and Fernandes, C. (2024). Zilucoplan: A Newly Approved Macrocyclic Peptide for Treatment of Anti-Acetylcholine Receptor Positive Myasthenia Gravis. Drugs Drug Candidates 3, 311–327. https://doi.org/10.3390/ddc3020018.

- Agarwala, A., Asim, R., and Ballantyne, C.M. (2024). Oral PCSK9 Inhibitors. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep. 26, 147–152. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11883-024-01199-2.

- Ballantyne, C.M., Gellis, L., Tardif, J.-C., Banka, P., Navar, A.M., Asprusten, E.A., Scott, R., Stroes, E.S.G., Froman, S., Mendizabal, G., et al. (2025). Efficacy and Safety of Oral PCSK9 Inhibitor Enlicitide in Adults With Heterozygous Familial Hypercholesterolemia: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2025.20620.

- Johns, D.G., Campeau, L.-C., Banka, P., Bautmans, A., Bueters, T., Bianchi, E., Branca, D., Bulger, P.G., Crevecoeur, I., Ding, F.-X., et al. (2023). Orally Bioavailable Macrocyclic Peptide That Inhibits Binding of PCSK9 to the Low Density Lipoprotein Receptor. Circulation 148, 144–158. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.063372.

- Landmesser, U., and Makhmudova, U. (2023). New Chapter in the PCSK9 Book: Oral Inhibition of PCSK9 Binding to the LDL Receptor With a Macrocyclic Peptide. Circulation 148, 159–161. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.123.065407.

- Zhao, X., Li, X., Zhang, S., Song, W., Fang, H., and Jin, K. (2025). Efficient Synthesis of Enlicitide Chloride through Convergent Solution-Phase and Hybrid Solution–Solid-Phase Strategies. Precis. Chem. https://doi.org/10.1021/prechem.5c00107.

About The Author

Gianni Cavallo, Ph.D., is a freelance medical and scientific writer based in Italy. He earned his M.Sc. in chemistry and pharmaceutical technologies from the University of Bologna and completed his Ph.D. at the Institut Charles Sadron (CNRS, Strasbourg, France). He has over 10 years of experience in research and development across academic and industrial settings, with a primary focus on hit-to-lead optimization and early preclinical development of macrocyclic peptides. He is the author of several high-impact peer-reviewed articles and is listed as an inventor on a patent for cyclic peptide inhibitors of IL-23.

Gianni Cavallo, Ph.D., is a freelance medical and scientific writer based in Italy. He earned his M.Sc. in chemistry and pharmaceutical technologies from the University of Bologna and completed his Ph.D. at the Institut Charles Sadron (CNRS, Strasbourg, France). He has over 10 years of experience in research and development across academic and industrial settings, with a primary focus on hit-to-lead optimization and early preclinical development of macrocyclic peptides. He is the author of several high-impact peer-reviewed articles and is listed as an inventor on a patent for cyclic peptide inhibitors of IL-23.