Designing Drugs For Women: Closing The Therapeutic Gap

By Sarah M. Temkin, MD, FACS; Melissa S. Wong, MD, MSHS; and Wendy B. Young, Ph.D.

Women’s health remains an underdeveloped frontier in drug innovation. Despite representing over half of the population, women remain underrepresented in the data, models, and design of research that drives biopharmaceutical discovery and development. Although biological, social, and structural factors influence drug safety, efficacy, and availability, sex-specific considerations have been customarily overlooked in the drug development pipeline. As a result, women have higher rates of adverse effects of approved products and limited effective therapeutic options for conditions more common among women. 1, 2 The growing momentum around women’s health — across policy, science, and funding — creates an opportunity to better align drug discovery with women’s health needs.

Policies Toward A New Paradigm

The historical exclusion of women from clinical research was rooted in the biomedical assumption that the 70 kg male represented the default human subject and a male mouse the default animal model. 3 Concerns that the hormonal fluctuations of menstrual cycling would introduce unnecessary variability into study populations and fears that enrollment of pregnant participants might potentially lead to a teratogenic fetal exposure provided a rationale for the exclusion of women from clinical trials. 4

Over the past three decades, progress has been made toward the inclusion of women in research. In 1993, the FDA rescinded guidance excluding women of childbearing age from clinical research. In the same year the NIH Revitalization Act mandated inclusion of women and minorities in federally funded clinical research. 5, 6 Development of most therapeutic interventions in use today began long before the NIH Sex as a Biological Variable policy was implemented in 2016. This policy established the expectation that female (as well as male) cells and animals be included in preclinical research when appropriate to the condition being studied. 7 The underrepresentation of female participants in studies and limited sex-stratified analyses of research has meant that certain medications in use today have been found to have different efficacy and toxicity in women than originally reported. 8, 9

In 2024, several policy proposals around women’s health received broad support. The Biden administration proposed a $12 billion Women’s Health Initiative to support research centered around the health needs of women. 10 A report of the National Academies of Science, Medicine, and Engineering commissioned by Congress recommended a $16 billion public investment in women’s health, including a new institute focused on female biology and physiology. 11 The future of these initiatives is uncertain at this time.

Women’s Health Considerations

The multidimensional biological construct of sex refers to anatomic, hormonal, genetic, and metabolic traits that interact at the cellular, organ, and system levels to influence phenotype and function. 12 These sex traits collectively influence pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics but remain poorly integrated into research design or analysis. Differences in skeletal muscle, water, and adipose distribution can alter absorption and distribution of drugs. 13 Variations in skin thickness and vascularity can influence the performance of patches and injectables across the menstrual cycle or life stages in women. 14 The hormonal environment influences protein binding and hepatic metabolism often controlling drug availability at the cellular level, and estrogen, progesterone, and androgen vary dramatically across the female lifespan. 15 The female immune system, regulated by the X chromosome and more active than that of the male, influences inflammation and consequently drug delivery and efficacy. 16 Greater insulin sensitivity, distinct lipid metabolism, and mitochondrial function can impact drug efficacy and adverse events. 2 Despite the multiplicity of biological distinctions, most clinical dosing remains based upon male physiology.

Many social factors, such as caregiving roles, economic constraints, and stigma, further therapeutic inequities. Gender norms shape behavior and interactions among patients and healthcare professionals. 3, 17 For example, reports of pain are more often attributed to mental health conditions than to physical causes in women compared to men. 18 Diagnostic delays are more common for nearly all chronic conditions in women, increasing the risk of missing therapeutic windows for early intervention. 19 Across age groups, women are more likely than men to be prescribed medications, putting them at increased risk of drug interactions. 20

Major Therapeutic Gaps

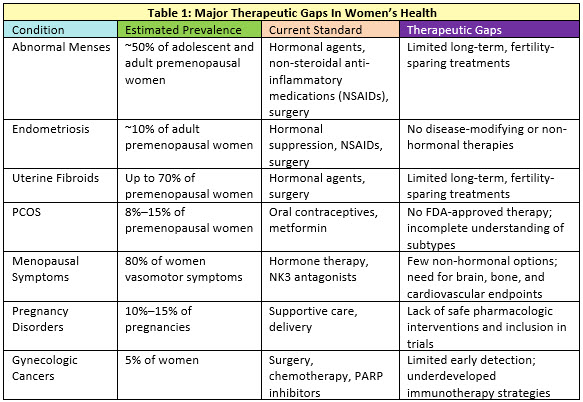

Significant therapeutic gaps persist across the spectrum of women’s health needs (Table 1). Gynecologic disorders, such as endometriosis, uterine fibroids, and polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), tend to affect women at younger ages. These conditions are characterized by long delays to diagnosis and have few efficacious therapies. 21 Autoimmune diseases disproportionately affect women and are also often diagnosed in younger women after significant delays. Many lack sex-specific treatment strategies despite differences in disease presentation and progression between men and women. Common symptoms of these disorders that affect premenopausal women include pain and infertility, which often interfere with educational attainment, caregiving, and workplace productivity. 22 The imbalance between burdens of disease and investment is clear — many of these disorders lack therapies that address the underlying pathophysiology.

Female reproductive life stages are infrequently considered in drug delivery although body composition, metabolic and enzymatic activity, and other marked physiologic changes occur during pregnancy and the menopausal transition. Pregnancy-related disorders, such as gestational diabetes and preeclampsia, not only pose immediate risks but also predispose women for chronic disease later in life. 23 The influence and interactions between diseases that primarily affect women during their reproductive years on health as they age is poorly understood. During midlife, symptoms of menopause are common, but few women receive treatment. 24

Following menopause, women experience an accelerated accumulation of chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndromes, and dementia, but the sex-specific biology of these disorders is inadequately understood. 25 Among older women, pelvic floor disorders, incontinence, and gynecologic cancers affect large numbers of women, yet they often go undiscussed in the healthcare environment due to stigma or shame around the symptoms. 23 These gaps highlight the need for more inclusive research, targeted therapies, and open dialogue in clinical care.

Innovation In Drug Discovery

Analysts project that the women’s health therapeutics sector will continue to grow, fueled by innovation in gynecologic diseases, menopause, and other conditions experienced commonly or differently by women26 Yet drug development programs focused on women’s health remain uncommon. Between 2007 and 2020, fewer than 4% of registered clinical trials were targeted gynecologic interventions. 27 The exclusion of pregnant women from clinical trials is common — even among recent Phase 4 trials, the majority (95%) explicitly exclude pregnancy. 28 An analysis of FDA approvals between 2009 and 2023 revealed only 7.2% treat female-specific conditions (e.g., menopausal symptoms) or diseases that disproportionately affect women (e.g., osteoporosis). Of these 43 agents, over half were specific to breast or gynecologic cancers, reflecting a paucity of innovation around non-oncologic conditions. 1

Vaginal and uterine drug delivery routes can provide direct access to local tissue targets and bypass first-pass hepatic metabolism yet have been underutilized. The acceptability of vaginal administration has been demonstrated. Novel polymer technologies and advanced manufacturing techniques offer new possibilities for vaginal and uterine drug delivery yet remain underexplored. 29

Advances in artificial intelligence and machine learning are now transforming nearly every stage of drug discovery, from target identification and molecular design to preclinical testing and clinical trial optimization. 30 At the cellular level, algorithms trained on datasets composed largely of male-derived cell lines may mischaracterize target biology or miss sex-differential pathways in immune, hepatic, or hormonal signaling. During animal model development, reliance on predominantly male rodents in toxicology data sets might skew AI-assisted safety predictions, leading to dosing recommendations that may not extrapolate accurately to female physiology. 31

While AI-enabled trial design and adaptive recruitment algorithms have been touted as a potential equalizer for women and others underrepresented in clinical research, they might also inadvertently reinforce male-majority participation patterns if gender and sex are not explicitly modeled. Finally, in post-marketing surveillance, natural language processing systems that detect adverse events from electronic health records may under-recognize female-predominant side effects (such as menstrual irregularities) since they have not previously been prioritized in studies intended to assess these outcomes.

Investment In Women’s Health Research And Drug Discovery

Federal research investment for conditions that affect women, and in particular female-specific and gynecologic diseases, remains disproportionately low. 11, 32 For most diseases that affect primarily one sex, federal funding favors those that primarily affect men. 33 This limited funding has significantly constrained the discovery of new biological targets for therapeutic development. When paired with the intrinsic risks of drug development — ranging from general safety challenges to additional requirements for women of childbearing potential — these constraints amplify the perceived investment risk. Strengthening support for foundational biological research would mitigate these uncertainties and foster more sustained investment.

After years of negligible private and corporate venture investment in women’s healthcare, the trend is shifting rapidly. Investors now recognize the vast, untapped market of women with unmet health needs and are actively working to capture this opportunity. Women are more likely than men to visit healthcare providers regularly and engage in self-care practices, with higher healthcare utilization and service adoption. 34 Women account for 85% of overall consumer spending and make 80% of family healthcare decisions, giving them an outsized influence on market demand and uptake. 35

Investment in all-women’s health (medicines, diagnostics, healthtech, and devices) reached $10.7 billion in 2024, up from $3.2 billion in 2019 (Figure 1).36 Investment in women-specific health conditions (contraception, fertility, maternal health, menopause, gynecology, women’s oncology), reached a record high of $2.6 billion in 2024 — a 3.2-fold increase from $813 million in 2019.36 Focusing on novel medicines in women-specific diseases and conditions, investment was <$100 million in 2019, increasing to $879 million in 2024.36 While this ~9-fold increase seems like a big shift, it is only a small fraction of the dollars going into all areas of drug discovery in biopharma and is less than 5% of all of healthcare investment. Early investments have focused on reproductive health, infertility, and pregnancy-related disorders, but attention is shifting toward areas of high unmet need like endometriosis, PCOS, and menopause care. Despite encouraging progress, work remains to be done to close the investment gap.

Another factor behind the growing momentum in women’s healthcare investment is the leadership of women venture capital partners. Although women currently represent only about 5% of VC partners, research shows that those in decision-making roles are driving a disproportionate share of the growth in this space. 37 With men representing the vast majority of investors, there is tremendous opportunity for them to play a larger role as well by collaborating with women to identify unmet needs, back innovative founders, and help accelerate progress across the sector.

Conclusion

The future of drug discovery must be equitable, evidence-based, and biologically informed. Designing drugs for women is both an unmet scientific need and a commercial opportunity. Bridging the women’s health gap in drug discovery requires an intentional shift beyond inclusion toward intentional design. By investing in sex-specific research, aligning clinical trial endpoints with women’s health priorities, investing in and researching relevant and new biological targets, and embracing novel delivery platforms, new therapeutic possibilities will become a reality. As momentum builds around the possibility for precision medicine for women, technological innovation also will accelerate, unlocking treatments that are safer, more effective, and more responsive to the health needs of women.

References

- Young WB. Women’s Healthcare: Call for Action. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 2024;67(11):8473-8480. https://doi.org10.1021/acs.jmedchem.4c01135

- Madla CM, Gavins FKH, Merchant HA, Orlu M, Murdan S, Basit AW. Let’s talk about sex: Differences in drug therapy in males and females. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2021;175:113804. https://doi.orghttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.addr.2021.05.014

- Barr E, Popkin R, Roodzant E, Jaworski B, Temkin SM. Gender as a social and structural variable: research perspectives from the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Translational Behavioral Medicine. 2023;14(1):13-22. https://doi.org10.1093/tbm/ibad014

- Institute of Medicine. Exploring the Biological Contributions to Human Health: Does Sex Matter? Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2001.

- National Institutes of Health Revitalization Act of 1993. US Government Printing Office; 1993.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Guideline for the study and evaluation of gender differences in the clinical evaluation of drugs; Federal Register Notice. 58. 1993:39406-39416.

- National Institutes of Health. Consideration of sex as a biological variable in NIH-funded research. 2015.

- U.S. Government Accountability Office. Drug Safety: Most Drugs Withdrawn in Recent Years Had Greater Health Risks for Women. Washington, DC; 2001.

- Zucker I, Prendergast BJ. Sex differences in pharmacokinetics predict adverse drug reactions in women. Biology of sex differences. 2020;11(1):32. https://doi.org10.1186/s13293-020-00308-5

- Harker J. President Biden Requests $12B for Research on Women’s Health. The NIH Catalyst. https://irp.nih.gov/catalyst/32/3/president-biden-requests-12b-for-research-on-womens-health; 2024.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2025. A new vision for women's health research: Transformative change at the National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2022. Measuring Sex, Gender Identity, and Sexual Orientation. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

- Soldin OP, Chung SH, Mattison DR. Sex differences in drug disposition. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2011;2011:187103. https://doi.org10.1155/2011/187103

- Brito S, Baek M, Bin B-H. Skin structure, physiology, and pathology in topical and transdermal drug delivery. Pharmaceutics. 2024;16(11):1403.

- Bosch EL, Sommer IEC, Touw DJ. The influence of female sex and estrogens on drug pharmacokinetics: what is the evidence? Expert Opinion on Drug Metabolism & Toxicology. 2025;21(6):637-647. https://doi.org10.1080/17425255.2025.2481891

- Farkouh A, Baumgärtel C, Gottardi R, Hemetsberger M, Czejka M, Kautzky-Willer A. Sex-related differences in drugs with anti-inflammatory properties. Journal of clinical medicine. 2021;10(7):1441.

- Heise L, Greene ME, Opper N, Stavropoulou M, Harper C, Nascimento M et al. Gender inequality and restrictive gender norms: framing the challenges to health. The Lancet. 2019;393(10189):2440-2454. https://doi.org10.1016/S0140-6736(19)30652-X

- Zhang L, Losin EAR, Ashar YK, Koban L, Wager TD. Gender Biases in Estimation of Others' Pain. J Pain. 2021;22(9):1048-1059. https://doi.org10.1016/j.jpain.2021.03.001

- Sun TY, Hardin J, Nieva HR, Natarajan K, Cheng R-f, Ryan P et al. Large-scale characterization of gender differences in diagnosis prevalence and time to diagnosis. medRxiv. 2023. https://doi.orgdoi: 10.1101/2023.10.12.23296976

- Boersma P, Cohen RA, Vahratian A. QuickStats: Percentage of Adults Aged>= 18 Years Who Were Prescribed Medication in the Past 12 Months, by Sex and Age Group-National Health Interview Survey, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(4):97. https://doi.orghttp://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6804a6

- Wijeratne D, Gibson JF, Fiander A, Rafii‐Tabar E, Thakar R. The global burden of disease due to benign gynecological conditions: A call to action. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2024;164(3):1151-1159. https://doi.org10.1002/ijgo.15211

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2024. Advancing Research on Chronic Conditions in Women. Washington, DC. The National Academies Press.

- Temkin SM, Barr E, Moore H, Caviston JP, Regensteiner JG, Clayton JA. Chronic conditions in women: the development of a National Institutes of health framework. BMC women's health. 2023;23(1):162. https://doi.org10.1186/s12905-023-02319-x

- Davis SR, Pinkerton J, Santoro N, Simoncini T. Menopause-Biology, consequences, supportive care, and therapeutic options. Cell. 2023;186(19):4038-4058. https://doi.org10.1016/j.cell.2023.08.016

- Rocca WA, Gazzuola-Rocca L, Smith CY, Grossardt BR, Faubion SS, Shuster LT et al. Accelerated Accumulation of Multimorbidity After Bilateral Oophorectomy: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(11):1577-1589. https://doi.org10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.08.002

- DiMarco M, Higgins A, Richardson S, Bruch JD, Marsella J. Investment Feminism and Women's Health. 2024.

- Steinberg JR, Magnani CJ, Turner BE, Weeks BT, Young AMP, Lu CF et al. Early Discontinuation, Results Reporting, and Publication of Gynecology Clinical Trials From 2007 to 2020. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2022;139(5). https://doi.org10.1097/AOG.0000000000004735

- Shields KE, Lyerly AD. Exclusion of Pregnant Women From Industry-Sponsored Clinical Trials. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013;122(5):1077-1081. https://doi.org10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182a9ca67

- Osmałek T, Froelich A, Jadach B, Tatarek A, Gadziński P, Falana A et al. Recent Advances in Polymer-Based Vaginal Drug Delivery Systems. Pharmaceutics. 2021;13(6):884.

- Özçelik R, van Tilborg D, Jiménez-Luna J, Grisoni F. Structure-Based Drug Discovery with Deep Learning. ChemBioChem. 2023;24(13):e202200776. https://doi.orghttps://doi.org/10.1002/cbic.202200776

- Gochfeld M. Sex Differences in Human and Animal Toxicology:Toxicokinetics. Toxicologic Pathology. 2017;45(1):172-189. https://doi.org10.1177/0192623316677327

- Temkin SM. To Improve Health in the United States, Focus on Women. JAMA. 2025;334(14):1225-1226. https://doi.orgdoi: 10.1001/jama.2025.14446

- Mirin AA. Gender disparity in the funding of diseases by the US National Institutes of Health. Journal of women's health. 2021;30(7):956-963. https://doi.orgdoi: 10.1089/jwh.2020.8682

- Taylor AK, Larson S, Correa-de-Araujo R. Women’s health care utilization and expenditures. Women's Health Issues. 2006;16(2):66-79. https://doi.orghttps://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2005.11.001

- Woodard M. Unlocking the trillion-dollar female economy. https://www.weforum.org/stories/2023/05/unlocking-trillion-dollar-female-economy: World Economic Forum; 2023.

- Venture Capital Investment in Women's Health Startups Reaching Record Highs. https://www.svb.com/news/company-news/venture-capital-investment-in-womens-health-startups-reaching-record-highs--silicon-valley-bank-releases-report/: Silicon Valley Bank; 2025.

- Ressi A. Women in Venture Capital. https://govclab.com/2025/08/07/women-in-venture-capital/; 2025.

About The Authors

Sarah M. Temkin, MD, is a gynecologic oncologist and clinician scientist with experience in drug development for female-specific malignancies, cancer prevention, and health equity. She served as the associate director for clinical research in the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health between 2021 and 2025. In that role, she developed and disseminated federal women’s health research priorities.

Sarah M. Temkin, MD, is a gynecologic oncologist and clinician scientist with experience in drug development for female-specific malignancies, cancer prevention, and health equity. She served as the associate director for clinical research in the NIH Office of Research on Women’s Health between 2021 and 2025. In that role, she developed and disseminated federal women’s health research priorities.

Melissa S. Wong, MD, MSHS, is the director of informatics and AI strategies and an assistant professor of maternal–fetal medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Her work focuses on designing and deploying artificial intelligence and clinical informatics tools that improve obstetric outcomes, reduce disparities in care, and strengthen real-world clinical decision making.

Melissa S. Wong, MD, MSHS, is the director of informatics and AI strategies and an assistant professor of maternal–fetal medicine at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center. Her work focuses on designing and deploying artificial intelligence and clinical informatics tools that improve obstetric outcomes, reduce disparities in care, and strengthen real-world clinical decision making.

Wendy B. Young, Ph.D., is a biotechnology and life sciences executive with over 30 years of experience in discovering and developing new medicines. She serves as a board member and scientific advisor to numerous biotech companies and is an advisor to GV (Google Ventures), contributing to the firm’s women’s healthcare initiatives. Previously, she was senior vice president of small molecule drug discovery at Genentech, where she led a research organization and advanced more than 25 drug candidates into clinical development.

Wendy B. Young, Ph.D., is a biotechnology and life sciences executive with over 30 years of experience in discovering and developing new medicines. She serves as a board member and scientific advisor to numerous biotech companies and is an advisor to GV (Google Ventures), contributing to the firm’s women’s healthcare initiatives. Previously, she was senior vice president of small molecule drug discovery at Genentech, where she led a research organization and advanced more than 25 drug candidates into clinical development.