Challenges And Opportunities For Reducing In Vivo Safety Assessment Testing With New Approach Methodologies

By Rakesh Dixit, Ph.D., DABT

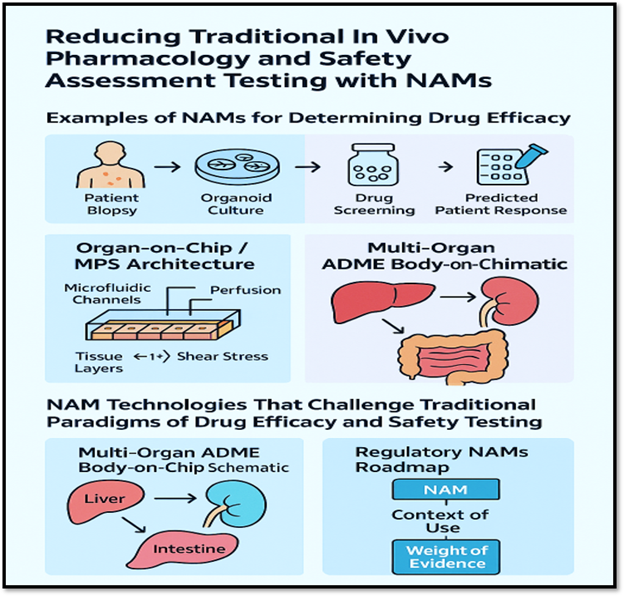

New approach methodologies (NAMs) refer to modern, non-animal scientific methods used to assess the safety, efficacy, or biological activity of drugs, chemicals, and other substances. They are designed to reduce, refine, or replace animal testing (the “3Rs”), while improving relevance to human biology.

Examples Of NAMs For Determining Drug Efficacy

Patient-derived organoids (PDOs): PDOs are 3D culture systems generated directly from patient tumor or normal tissue biopsies. They retain the genetic, molecular, and histological characteristics of the source tissue, making them valuable tools for studying drug efficacy and resistance mechanisms, as well as for applications in personalized medicine.

PDOs retain the driver mutations, copy number changes, and the patient's tumor. They can maintain intratumoral heterogeneity (clonal diversity) better than long‐passaged lines. Compared to vivo models (e.g., patient-derived xenografts [PDXs]), PDOs offer a faster turnaround, lower cost, and suitability for multiple drug screenings. Because they derive from individual patients, they offer the possibility of “avatar” or ex vivo sensitivity testing to guide therapy. Some example case studies are as follows:

- In colorectal cancer, a study of rectal cancer PDOs showed ~86 % accuracy in recapitulating patient response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation.

- In breast cancer, reviews highlight PDOs as a promising tool for drug screening, personalized therapy, and biomarker development.

- In upper GI cancers (gastric, esophageal), there’s growing use of PDO + PDX models because prior models (cell lines) had poor translation.

Microphysiological systems (MPS)/organs-on-chips (MPS/OoC): MPS and OoCs are engineered in vitro platforms that recapitulate key structural, mechanical, perfusion/flow, and functional features of human tissues or organs (or multiple linked organs). Typical components include microfluidic channels; living human (or human-derived) cells arranged in three-dimensional or physiologically relevant architectures; controlled flow, often a barrier or interface (e.g., epithelium/endothelium); mechanical cues (such as shear and stretch); and, in some cases, inter-organ connectivity.

The aim is to mimic human organ and tissue behavior more faithfully than conventional 2D cell cultures or simple 3D spheroids and to provide alternatives/complements to animal models. Because they more closely approximate human physiology, these systems have considerable promise for drug discovery, particularly for assessing efficacy; pharmacokinetics (PK)/pharmacodynamics (PD); absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion (ADME); and toxicity in a human-relevant manner.

In a 2023 review,1 several device examples are described: heart-on-a-chip assessing antiarrhythmic efficacy of verapamil; liver-on-a-chip recapitulating nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) to test elafibranor; tumor-on-a-chip for breast cancer to test epirubicin/paclitaxel.

Multi-organ 18-organ system: A recent report in 20252 describes linking a vascular system and excretion modules in a body-on-a-chip device, which is relevant to drug efficacy and ADME‐influenced responses.

High-content 3D spheroid co-cultures: These are faster, scalable phenotypic efficacy screens that surpass 2D lines for many tumor types, often used as feeders for PDO/MPS.

In silico/qualitative systems pharmacology (QSP) and AI-assisted models: These are mechanism-based simulators and ML models that integrate PK/PD, target engagement, and pathway effects and are increasingly linked to adverse outcome pathways (AOPs) and omics readouts for decision support.

NAM Technologies That Challenge Traditional Paradigms Of Drug Efficacy And Safety Testing

PDOs retain the genetic, epigenetic, and phenotypic fidelity of human tissues, reflecting individual variability in drug response (e.g., tumor organoids used to predict chemotherapy response). PDOs enable longitudinal tracking of tumor evolution and resistance mechanisms, providing mechanistic insights that 2D or animal systems cannot.

OoCs integrate microfluidics, mechanical forces, and 3D architecture to mimic organ-level functions (e.g., heart-on-chip for cardiotoxicity testing, liver-on-chip for metabolic testing). OoCs simulate dynamic physiological environments — including shear stress, cyclic strain, and perfusion — enabling real-time monitoring of biomarkers, cytokines, and gene expression under physiologic flow conditions.

Animal use is resource-intensive, ethically contentious, and slow. Regulatory frameworks, such as those that have traditionally adhered to International Council for Harmonization (ICH) guidelines regarding in vivo data for safety justification, play a critical role in establishing industry standards. NAMs align with the 3Rs principles and the FDA Modernization Act 2.0, which enables the use of non-animal data to support IND submissions. By reducing reliance on animal testing, NAMs could accelerate drug development while enhancing translatability and reproducibility. However, the application of NAMs has substantial challenges:

- Standardization and validation: The lack of harmonized protocols and reproducibility across laboratories impedes regulatory adoption.

- Incomplete systemic representation: Single-organ models cannot yet capture immune, endocrine, or metabolic cross talk.

- Scalability: Manufacturing and throughput limitations hinder use in large-scale screening.

Limitations Of Current Omics-Based NAMs In Capturing Systemic Toxicity

Although NAMs — such as organoids, organs-on-chips, MPS, and in silico models — have transformed preclinical science, they still face significant scientific, technical, and regulatory constraints.

Biological and systemic limitations with formidable challenges include:

- Lack of full-organism complexity: Most NAMs model a single organ or pathway; they cannot yet replicate immune, endocrine, or neurohumoral cross talk that is essential for predicting systemic toxicity or therapeutic index.

- Incomplete ADME representation: Drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion depend on multi-organ interactions (e.g., liver–kidney–gut interplay). Single-organ models rarely capture these dynamics, limiting prediction of clearance, bioaccumulation, or metabolite-driven toxicity.

- Absence of chronic exposure data: Many NAMs are designed for short-term experiments; chronic or cumulative toxicities (e.g., fibrosis, carcinogenesis) are challenging to assess.

- Limited immune competence: Organoids and OoCs typically lack fully functional immune or inflammatory components, constraining evaluation of immunogenicity, cytokine release, or autoimmunity risk.

- Reproducibility and standardization: Variability in device materials, flow parameters, and cell sources makes inter-laboratory comparability difficult. The lack of validated reference standards undermines regulatory confidence.

- Throughput and scalability: Most NAMs are low-throughput and labor-intensive, which is unsuitable for early discovery screening or dose-response studies requiring large data sets.

- Data integration challenges: Omics, imaging, and microfluidic data are complex; bioinformatic harmonization across platforms remains underdeveloped.

- Manufacturing and cost: High costs for chip fabrication, microfluidic pumps, and human cell sourcing limit widespread adoption.

- The adoption of NAMs in scientific research has gained increasing attention from regulatory bodies worldwide.

- Regulatory and validation barriers: Although organizations, such as the FDA, European Medicines Agency (EMA), and Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), express support for NAMs, relatively few models have attained formal validation or have been incorporated into official guidelines (e.g., OECD test guidelines). The key challenges for regulatory acceptance are as follows:

- Lack of defined acceptance criteria: Regulators still require bridging to in vivo endpoints — such as no adverse effect level (NOAEL), highest non-severely toxic dose (HNSTD), or development/reproductive endpoints (DART) outcomes—before accepting NAM data for IND/biologics license application (BLA) submissions.

- Risk of overinterpretation: NAMs can mimic human biology but not replace empirical whole-animal data when safety margins, biodistribution, or long-term effects are uncertain.

- Ethical and societal considerations for human-derived tissue sourcing: Ethical sourcing, consent, and biobanking for organoids may involve privacy or equity issues.

- Data ownership and standardization: The integration of patient-derived data sets raises complex regulatory and ethical questions regarding reproducibility and the use of proprietary data.

- Continuing value of preclinical (in vivo) studies: Despite progress in NAMs, in vivo animal studies remain indispensable for several scientific and regulatory reasons.

- Systemic and multiorgan integration: Whole-animal models uniquely capture physiological integration, including metabolism, hemodynamics, and compensatory mechanisms, which is critical for interpreting drug exposure, response, and off-target effects. They enable the assessment of organ cross talk (e.g., hepatic metabolism impacting renal or CNS toxicity), which is not possible in isolated NAM systems.

- Chronic, reproductive, and developmental safety: Long-term toxicity, carcinogenicity, and DART require systemic exposures over time that NAMs cannot yet sustain. Animal studies remain the regulatory gold standard under ICH M3(R2), S5(R3), and S6(R1) for establishing NOAEL/HNSTD and defining safe starting doses (minimally anticipated biologic effect level [MABEL]/human equivalent dose [HED]).

- Translational pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD): In vivo models are essential for PK–PD correlation, tissue distribution, and identifying exposure thresholds for efficacy vs. toxicity. They provide insight into species-specific metabolic pathways, enabling the extrapolation of human risk via modeling (e.g., PBPK, allometric scaling).

Therapeutic Areas That Are Well-Suited For Integration With NAMs

1. Oncology and immuno-oncology: potentially suitable

- PDOs and tumor-on-chip systems preserve the heterogeneity, 3D architecture, and microenvironment of individual tumors.

- They allow for personalized drug screening, resistance mechanism identification, and combination therapy testing.

- Immune-tumor co-culture MPS systems capture immune checkpoint biology.

- Examples: PDOs for colorectal, pancreatic, and breast cancer drug screening; tumor–immune microfluidic models used to evaluate bispecific antibodies; and antibody-drug conjugate (ADC) payload activity

2. Hepatotoxicity and metabolic disorders: suitable

Human liver-on-chip models mimic hepatocyte polarity, bile canaliculi formation, and CYP450 enzyme activity, enabling prediction of drug-induced liver injury (DILI) and metabolism-based toxicities. This also may allow integration of multi-organ systems (e.g., gut–liver axis) for metabolic drug evaluation.

3. Cardiovascular and CNS disorders: suitable

Cardiac MPS using induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC)-derived cardiomyocytes reproduces electrophysiological responses and contractility, which helps detect QT prolongation, arrhythmias, or off-target effects. Blood-brain barrier (BBB) and brain-on-chip systems enable evaluation of neurotoxicity, neuroinflammation, and drug penetration.

4. Infectious diseases and inflammation: suitable

MPS can recreate host–pathogen interactions in lung, gut, and skin tissues and enable testing of antivirals, vaccines, and innate immune modulators under physiologically relevant conditions.

5. Reproductive and developmental toxicology: suitable

Traditional animal models show species-specific developmental differences. Placenta-on-chip and endometrium-embryo co-cultures may improve prediction of maternal–fetal transfer, teratogenicity, and implantation effects.

6. Biologics and complex modalities (ADCs, antibody oligonucleotide conjugates [AOCs], cell and gene therapies): suitable

NAMs bridge the translational gap for species-limited targets (e.g., the neonatal Fc receptor [FcRn] complement immune receptors) and enable human-cell-specific assessments of payload toxicity, immune activation, and off-target effects.

7. Rare and personalized diseases: suitable

Patient-derived iPSC or organoid models enable mechanistic studies and drug screening when animal models are unavailable or poorly predictive.

- Examples: Cystic fibrosis airway organoids for cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) modulators and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) or Parkinson’s disease iPSC-derived neural models for disease-specific drug evaluation

Practical Considerations For Biologics

Given a focus on biologics where in vivo studies are less predictable, here are how the FDA’s NAMs directive/principles touch those areas (see key regulatory documents)

- Allowing NAMs instead of traditional animal safety if justified: The road map explicitly suggests that for monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) (and by extension other biologics) where animal models are less predictive (e.g., immunogenicity, species-specific binding, FcRn biology), NAMs (human-cell-based systems + in silico) may substitute for parts of the preclinical package.

- Weight-of-evidence (WoE) approach: The FDA emphasizes that NAM data should be integrated into a WoE package. That means, for your interest (e.g., novel AOCs or bispecifics), you will need to frame how the NAM mechanistically links (mechanism of action [MOA], ADME, target engagement) and how it fits with any supporting in vivo or historical human data.

- Qualification/validation of NAMs: As with analytical methods or biomarkers, the agency expects clear justification of context-of-use, reproducibility, relevance, and human-predictive validity for any NAM proposed to replace animal testing.

- Incentives and early engagement: From a strategy perspective, engaging the FDA early (pre-IND/clinical trial application [CTA]) to discuss the NAM strategy, context-of-use, bridging to animal or human data, and how WoE will be assembled, is wise. The road map suggests that sponsors using NAM-first approaches may gain review advantages.

- Translational risk for newer modalities: While the policy is permissive, in practice, NAM adoption for high-risk areas (e.g., reproductive toxicity, immune-on-target/off-target toxicity, species-specific biologic modes) remains challenging. The literature emphasizes that many NAMs are not yet fully validated for quantitative decision-making (NOAEL, etc.).

- International harmonization: Given the interest in IND/BLA/CTA strategies, note that the road map also references ICH and global alignment (e.g., ICH S6, S1B, S5[R3]). The ability to use NAMs may therefore also influence cross-region comparability and bridging strategies.

References

- Marx U, et al. Emerging trends in organ-on-a-chip systems for drug screening. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2023.

- Wang J, et al. An eighteen-organ microphysiological system coupling a vascular network and excretion system for drug discovery. Microsyst Nanoeng. 2025 May 14;11(1):89. doi: 10.1038/s41378-025-00933-3. PMID: 40368882; PMCID: PMC12078732.

Further Reading

- OECD. Guidance Document on Good In Vitro Method Practices (GIVIMP). OECD Series on Testing and Assessment. 2018.

- U.S. FDA Modernization Act 2.0, Pub. L. No. 117-286. 2022.

- Schutgens F, et al. Patient-derived organoids in precision oncology. Nat Rev Cancer. 2022.

- NCATS Tissue Chip Testing Centers (TCTC) Initiative. NIH/NCATS. 2024.

- CEN-CENELEC Roadmap on Microphysiological Systems Standardization. 2024.

- ISSCR Guidelines for Stem Cell Research and Clinical Translation. 2023.

- OECD Draft Guidance on Good In Vitro Reporting Standards (GIVReSt). 2025.

Key Regulatory Documents

The FDA’s “Roadmap to Reducing Animal Testing in Preclinical Safety Studies” (2025) describes how the agency plans to reduce reliance on animal testing, using NAMs.

Yao J, Peretz J, Bebenek I, et al. FDA/CDER/OND Experience With New Approach Methodologies (NAMs). International Journal of Toxicology. 2025;0(0). doi:10.1177/10915818251384270

About The Author

Rakesh Dixit, Ph.D., DABT, is a board-certified toxicologist and has a Ph.D. in pharmacology/toxicology. He is a globally recognized biopharmaceutical executive and scientist with over 30 years of experience leading drug discovery, safety assessment, and translational development across biologics and ADCs. As President & CEO of BionaviGen Oncology and cofounder/CSO of Regio Biosciences, he drives innovation in oncology and cardiovascular therapeutics. Formerly the Vice President of Global Biologics Safety Assessment at AstraZeneca, Dixit played a pivotal role in advancing over 10 marketed biologics (including Imfinzi, Fasenra,Ineblizumab, Antfrolumab, and Brodalumab) and over 100 IND/BLA submissions. Honored with the World ADC Award (2020) and PharmaVOICE 100 (2015), he is a trusted global advisor to biopharma companies and investors across the U.S., Europe, and Asia.

Rakesh Dixit, Ph.D., DABT, is a board-certified toxicologist and has a Ph.D. in pharmacology/toxicology. He is a globally recognized biopharmaceutical executive and scientist with over 30 years of experience leading drug discovery, safety assessment, and translational development across biologics and ADCs. As President & CEO of BionaviGen Oncology and cofounder/CSO of Regio Biosciences, he drives innovation in oncology and cardiovascular therapeutics. Formerly the Vice President of Global Biologics Safety Assessment at AstraZeneca, Dixit played a pivotal role in advancing over 10 marketed biologics (including Imfinzi, Fasenra,Ineblizumab, Antfrolumab, and Brodalumab) and over 100 IND/BLA submissions. Honored with the World ADC Award (2020) and PharmaVOICE 100 (2015), he is a trusted global advisor to biopharma companies and investors across the U.S., Europe, and Asia.