Antibody–Drug Conjugates 3.0: A New Era Of Precision Engineering In Oncology

By Mahmoud Khatib Al-Ruweidi

The concept of targeting diseased cells for elimination while preserving healthy tissue has existed prior to advancements in modern biotechnology. Paul Ehrlich’s early 20th‑century proposal that drugs might act as “selective poisons” has remained an aspiration for pharmacotherapy. Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs) are contemporary embodiments of this concept. An ADC comprises a monoclonal antibody that recognizes a tumor‑associated antigen, a cytotoxic payload, and a chemically engineered linker. Through this three‑component architecture, highly potent small molecule toxins can be delivered preferentially to cells expressing the target antigen while systemic exposure is minimized.1

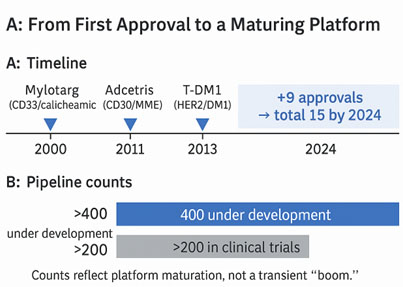

Clinical adoption of ADCs has proceeded in iterative waves. The proof of concept came with the approval of gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) in 2000,2 but this first‑generation therapy suffered from immunogenicity and unstable linkers that caused premature payload release and a narrow therapeutic window. Since 2019, nine additional ADCs have obtained regulatory approval, bringing the total number of globally marketed ADCs to 15 by 2024.3 The developmental pipeline has expanded accordingly. More than 400 ADCs are under active development and over 200 are in clinical trials.4

The Generational Evolution Of ADC Technology

The progression of ADC technology is best understood as a three-generation arc, where the specific failures of each era became the precise design priorities for the next.

ADC 1.0: Pioneering Efforts And Foundational Limitations (c. 2000–2010)

The first generation is defined by its archetype, gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg).5 This was built on three foundations:

- Antibody: It used a chimeric (part-mouse) antibody that provoked immunogenic responses (human anti-chimeric antibodies, or HACA), limiting its efficacy and potential for repeat dosing.6

- Linker: It had an acid-sensitive hydrazone linker that was intended to cleave in the acidic environment of the lysosome (pH 4.5-6.0). However, it proved fatally unstable in the neutral pH of blood (pH approx 7.4), leading to catastrophic premature payload release.7

- Conjugation: Its stochastic conjugation method targeted surface lysine residues, resulting in a highly heterogeneous and poorly characterized mixture of ADC species.8

The clinical consequence of this design was the systemic release of the highly potent calicheamicin payload, causing severe and often fatal off-target toxicities, particularly hepatotoxicity and veno-occlusive disease.9 The therapeutic window was almost nonexistent, leading to its market withdrawal in 2010.

ADC 2.0: Improving The Therapeutic Index (c. 2011–2019)

The second generation of ADCs addressed the limitations of ADC 1.0, resulting in two landmark approvals that validated the entire ADC concept: brentuximab vedotin and ado-trastuzumab emtansine.10

The improvements were substantial:

- Antibody: Humanized or fully human antibodies were used, which drastically eliminated the immunogenic responses.

- Payloads: New, highly potent payload classes were introduced, such as microtubule inhibitors, auristatins (e.g., MMAE in Adcetris), and maytansinoids (e.g., DM1 in Kadcyla).11

- Linkers: This era realized the critical divergence into two stable, but strategically distinct, linker philosophies. This includes protease-cleavable linkers (e.g., Val-Cit in Adcetris) that stay plasma-stable but are cut by lysosomal cathepsin B to release membrane-permeable MMAE, enabling a bystander effect. In addition, non-cleavable linkers (e.g., MCC in Kadcyla) remain intact until antibody proteolysis, which yields a charged lysine-DM1 adduct that can’t exit the cell, maximizing stability but foregoing bystander killing.12

This split led to a strategic choice in ADC design. Non-cleavable "containment" linkers (e.g., Kadcyla) are preferred for targets with low healthy-tissue expression to minimize bystander effects, while cleavable "area-of-effect" linkers (e.g., Adcetris) address antigen heterogeneity. However, ADC 2.0 still used random conjugation to lysines or cysteines, resulting in heterogeneous products (drug-to-antibody ratio [DAR] 0–8) where high-DAR species were hydrophobic, aggregated, and rapidly cleared, thus narrowing the therapeutic window and complicating pharmacokinetics.

ADC 3.0: The Paradigm Of Precision And Potency (c. 2019–Present)

The current generation, ADC 3.0, is defined by its solution to the heterogeneity problem. Some archetypes include trastuzumab deruxtecan (Enhertu), polatuzumab vedotin (Polivy), and enfortumab vedotin (Padcev).13

The defining features of this era are:

- Homogeneity: Site-specific conjugation technologies are widely adopted to produce "deterministic" ADCs with a uniform, defined DAR (often 2 or 4). Polatuzumab vedotin, for instance, uses engineered cysteines to achieve a uniform DAR.14

- Advanced Linkers: Linkers and payloads are co-engineered to actively manage biophysical properties, such as incorporating hydrophilic polyethylene glycol (PEG) moieties to prevent aggregation.15

- New Payloads: Novel payload classes are introduced, such as the topoisomerase I inhibitors deruxtecan (in Enhertu) and SN-38 (in Trodelvy).16

ADC 3.0 weaponized the bystander dial. Enhertu, for instance, pairs a cleavable linker with a membrane-permeable deruxtecan (DXd) payload to excel in heterogeneous, low-antigen tumors (e.g., HER2-low breast cancer). In addition, ADC 3.0 overturns the “DAR paradox.” The issue wasn’t high DAR (>4), but high hydrophobicity. Through co-engineering hydrophilic linkers/payloads, programs like Enhertu and sacituzumab govitecan (Trodelvy) run at ~8 DAR without aggregation or rapid clearance, delivering more payload per antibody and greater potency.17

Innovations In Linker Chemistry And Controlled Payload Release

The linker is crucial to ADC’s therapeutic index. It must remain stable in circulation but quickly cleave after internalization, a challenge for earlier generations. ADC 3.0 addresses this with chemistries that combine plasma stability, tumor-specific triggers, and self-immolative release, improving the efficacy and reducing off-target toxicity.15

Strategic Design: Cleavable vs. Non-Cleavable Linkers

The first strategic choice in linker design is the release mechanism, which dictates the ADC's entire pharmacological profile, particularly its bystander effect potential.

Cleavable linkers (dominant; >80% of approvals):

- Protease-sensitive (e.g., Val-Cit): high lysosomal selectivity and plasma stability; the workhorse class (e.g., Adcetris, Padcev, Polivy).18

- Acid-sensitive (hydrazones): exploit the endosomal/lysosomal pH but suffer plasma hydrolysis; largely retired (e.g., early Mylotarg).18

- Glutathione-sensitive (disulfides): reduced intracellularly; used in agents like Elahere.18

Non-cleavable linkers (e.g., 4-[N-maleimidomethyl] cyclohexane-1-carboxylate [MCC] in T-DM1):

- Payload is released only after antibody proteolysis (often as a charged amino-acid–payload adduct), minimizing off-target exposure.18

- Trade-off: Excellent plasma stability but no bystander effect. Its selection is best when target expression is homogeneous and safety margins are paramount.18

Advanced Molecular Engineering: Spacers, Kinetics, And Solubility

Beyond the cleavage trigger, ADC 3.0 linkers incorporate multifunctional components to precisely control payload release and modulate the conjugate's biophysical properties.

Self-immolative spacers (e.g., para-aminobenzyloxycarbonyl [PABC]): After trigger cleavage, the spacer self-immolates to release the native, fully active payload. Tuning spacer electronics control release kinetics — fast for rapid kill, slower for deeper tumor penetration.19

Hydrophilic “stealth” linkers: The linker is a pharmacokinetics (PK) modulator, not a bridge. Adding polyethylene glycol (PEG) or charged groups counters hydrophobic payloads (especially at high DAR), reduces aggregation, preserves antibody-like behavior, and extends half-life, which enables high-DAR designs (e.g., Enhertu).19

Maleimide stability: First-gen thiol–maleimide bonds can undergo retro-Michael exchange, causing premature release/albumin transfer.20 ADC 3.0 uses self-hydrolyzing or alternative maleimides to “lock” the bond, improving plasma stability and limiting off-target exposure.

Precision DAR Control Via Site-Specific Conjugation

The Criticality Of DAR: From Heterogeneous Mixtures To Homogeneous Therapeutics

ADC 3.0’s mandate is to eliminate heterogeneity. Legacy stochastic conjugation across 80 lysines or eight cysteines (after disulfide reduction) creates statistical mixtures. A single vial can span DAR 0–8, with significant pharmacological consequences.

- High-DAR species (e.g., DAR 6-8): These molecules are highly hydrophobic, which causes them to aggregate. They are rapidly cleared from circulation by the liver and spleen and contribute disproportionately to off-target toxicity.

- Low-DAR species (e.g., DAR 0-2): They are inefficient, "diluting" the therapeutic effect by competing with more potent species for antigen binding.

This heterogeneity created a statistical nightmare for drug development. It is impossible to conduct true structure-activity relationship (SAR) studies on a mixture; if a batch fails, the specific problematic subpopulation is unknown. Furthermore, it creates a massive chemistry, manufacturing, and controls (CMC) and regulatory burden in proving lot-to-lot consistency.

ADC 3.0 makes DAR deterministic: It delivers homogeneous, site-specific ADCs with a defined DAR (often 2 or 4), so every molecule is identical.

The payoff: predictable PK, consistent efficacy, and improved safety, turning ADCs into a mature, investable platform that finally enables true rational design.

The ADC 3.0 Toolkit: Key Site-Specific Platforms

To achieve homogeneity, a powerful toolkit of site-specific conjugation technologies has been developed:

- Engineered cysteine residues (e.g., thiol-engineered monoclonal antibodies [THIOMABs]): This platform, pioneered by Genentech, uses genetic engineering to introduce reactive cysteine residues at specific, solvent-accessible sites on the antibody backbone. During the manufacturing, mild reducing conditions are used to target only these engineered thiols (leaving native disulfides intact), allowing for conjugation at a precise location. This reliably yields a homogeneous product, typically with a DAR of 2. Polatuzumab vedotin (Polivy) is a clinical example of this technology.21

- Enzymatic conjugation: This approach enables precise, site-specific attachment: microbial transglutaminase (mTG) couples payloads to an engineered Fc glutamine, forming a stable bond away from the fragment antigen-binding (Fab), while glycan remodeling edits the conserved fragment crystallizable (Fc) N-glycan to install a bioorthogonal handle (e.g., azide) for click chemistry platforms, such as SMARTag or AJICAP, yielding highly uniform DAR 2 products.22

- Unnatural amino acids (nnAAs) and click chemistry: This approach employs synthetic biology techniques to introduce a non-canonical amino acid, such as para-azidomethyl-L-phenylalanine, featuring a distinct bio-orthogonal functional group (e.g., azide or alkyne) at a defined position within the antibody sequence during expression. This "unnatural" handle allows for a highly specific and efficient copper-free click reaction with a complementary-functionalized payload, forming an exceptionally stable triazole linkage without disturbing any native protein function.23 This offers ultimate control over conjugation.

- Disulfide re-bridging: This method specifically targets native interchain disulfide bonds. A bifunctional reagent is employed to reduce the disulfide bond and subsequently "re-bridge" the pair of cysteine thiols with a stable linker that also incorporates the desired payload.24 This approach enables the generation of a homogeneous DAR 4 ADC, while preserving the native quaternary structure of the antibody.

Translational Toxicology And Safety-By-Design

An ADC's success depends on its therapeutic index. As linkers stabilized and conjugation improved, research shifted toward addressing subtler toxicities, reflecting translational toxicology's evolution into a proactive, safety-by-design approach.

Deconstructing ADC Toxicity: A Unique Pharmacological Profile

ADC-related toxicities are complex and mechanistically distinct from conventional chemotherapy. They are broadly categorized into two types:

- On-target, off-tumor toxicity: This happens when healthy tissues that express the target antigen even at low levels are affected by the ADC. This is a core risk for non-tumor-exclusive targets. For instance, Trop-2–directed ADCs (e.g., Trodelvy) can cause gastrointestinal adverse events (diarrhea, mucositis) because normal gut epithelium expresses low-level Trop-2.25

- Off-target, payload-driven toxicity: This toxicity arises when the payload affects healthy tissues, either due to premature release from an unstable linker — a characteristic of first-generation ADCs — or through non-specific uptake of the intact ADC by cells within the reticuloendothelial system, such as those in the liver.26 This typically results in chemotherapy-like side effects, such as neutropenia and thrombocytopenia, since bone marrow progenitors are highly sensitive to cytotoxic agents.

The Emergence Of Payload-Specific Class Toxicities

The ADC 3.0 era highlights a payload-centric safety approach, as highly stable linkers have revealed toxicities linked to the payload itself. ADCs using the same payload class often present similar dose-limiting toxicities, independent of antibody target. For example, monomethyl auristatin F (MMAF)-based ADCs commonly cause keratopathy and blurred vision, while topoisomerase I inhibitor payloads such as deruxtecan (Enhertu) can lead to serious ILD/pneumonitis.

The Rise Of Predictive Toxicology And Safety-By-Design

The maturity of the ADC field is reflected in its response to these toxicities, which has been to co-develop the drug and its clinical management protocol.

Predictive models: Because rodent studies miss human-specific liabilities, programs pair humanized in vivo and human-relevant in vitro systems with mechanistic modeling. Humanized mice expressing the human target (e.g., TROP2/HER2) reveal on-target/off-tumor risks and quantify how expression and internalization drive local payload exposure.27 Three-dimensional organoids/spheroids capture bystander effects; bone-marrow colony-forming unit (CFU) assays estimate myelosuppression; organ-specific systems (corneal epithelium, alveolar co-cultures) flag class-typical toxicities early.

Computational exposure modeling: Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) (± quantitative systems pharmacology [QSP]) maps intact ADC, deconjugated antibody, and released payload across organs.28 Models integrate DAR distribution, linker cleavage, and payload permeability/hydrophobicity to forecast organ area under the curve (AUC), identify hot-spot tissues, and set exposure guardrails. Starting doses/escalation increasingly follow minimum anticipated biological effect level (MABEL)-style criteria informed by these simulations rather than no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL) alone.

Safety-by-design levers: Target selection favors high tumor, normal expression, rapid internalization, and minimal shedding; epitope/affinity are tuned to avoid vascular trapping. Fc engineering (e.g., IgG4 S228P; LALA/PGLALA) attenuates unwanted antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC)/complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC) with de-immunization/glycan work, as needed. Linker–payload choices modulate bystander: for higher normal-tissue risk, use non-cleavable linkers or impermeable payloads (e.g., MMAF); for heterogeneous tumors with low normal-tissue risk, allow controlled bystander (cleavable + permeable payload, e.g., monomethyl auristatin E [MMAE]/DXd) under PBPK-defined caps.29 Hydrophilic linkers/PEG and site-specific conjugation temper high-DAR hydrophobicity and PK variability.

From models to protocol: PBPK limits inform starting dose and increments; preclinical organ signals translate into baseline testing and scheduled monitoring (e.g., ophthalmology for MMAF; interstitial lung disease [ILD] surveillance for topo-I). Dose-mods, premeds, and re-challenge rules are prespecified; step-up dosing or extended infusions are used when C_max drives toxicity.

Future Directions: Experimental Payloads And Novel Architecture

Research is exploring payload classes beyond traditional cytotoxic, but these approaches remain largely preclinical or in early phase trials. Degrader‑antibody conjugates (DACs) seek to deliver proteolysis‑targeting chimeras (PROTACs) to tumor cells.30 As of mid‑2025 there are fewer than two dozen DAC candidates in development. Only ORM‑6151 has reached Phase 1 evaluation, and earlier programs, such as ORM‑5029 and ABBV‑787, have been discontinued.31 Stimulator of interferon genes (STING) agonist ADCs aim to trigger innate immune signaling within tumors. Daiichi Sankyo’s DS‑3610 entered a first‑in‑human Phase 1 trial in November 2025, and no clinical efficacy or safety data have yet been reported. Dual‑payload and bispecific ADCs attempt to broaden antitumor activity and overcome resistance by linking two payloads or targeting two antigens simultaneously. These architectures are conceptually attractive but are still in early clinical or preclinical stages; the first dual‑payload ADC to receive IND clearance, KH815, has not yet been administered to patients. Preclinical studies show that dual‑payload designs face challenges in controlling DAR and pharmacokinetic balance, and experiments have not consistently demonstrated superior efficacy over single‑payload ADCs. It is therefore premature to portray these modalities as established therapeutic classes.

Final Remarks

The evolution of antibody–drug conjugates illustrates how advances in antibody engineering, linker chemistry, and conjugation technology can incrementally refine a therapeutic modality. Modern ADCs achieve homogeneity, stability, and potency that were unattainable two decades ago. At the same time, clinical experience has revealed payload‑specific toxicities and underscored the need for proactive safety engineering. While exploratory platforms — such as DACs, STING agonist ADCs, and dual‑payload constructs — generate excitement, they remain investigational. Rigorous preclinical validation and carefully designed early‑phase trials will determine whether these concepts translate into clinically meaningful benefits. Maintaining a measured, evidence‑based perspective will ensure that the next generation of ADCs fulfills the promise of selective, potent, and safe targeted therapy.

References

- Wang, R.; Hu, B.; Pan, Z.; Mo, C.; Zhao, X.; Liu, G.; Hou, P.; Cui, Q.; Xu, Z.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Zhao, L.; He, M.; Wang, Y.; Fu, C.; Wei, M.; Yu, L. Antibody–Drug Conjugates (ADCs): Current and Future Biopharmaceuticals. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2025, 18 (1), 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13045-025-01704-3.

- Liu, K.; Li, M.; Li, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, Z.; Tang, Y.; Yang, M.; Deng, G.; Liu, H. A Review of the Clinical Efficacy of FDA-Approved Antibody‒drug Conjugates in Human Cancers. Mol. Cancer 2024, 23 (1), 62. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12943-024-01963-7.

- Fong, J. Y.; Phuna, Z.; Chong, D. Y.; Heryanto, C. M.; Low, Y. S.; Oh, K. C.; Lee, Y. H.; Ng, A. W. R.; In, L. L. A.; Teo, M. Y. M. Advancements in Antibody-Drug Conjugates as Cancer Therapeutics. J. Natl. Cancer Cent. 2025, 5 (4), 362–378. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jncc.2025.01.007.

- Metrangolo, V.; Engelholm, L. H. Antibody–Drug Conjugates: The Dynamic Evolution from Conventional to Next-Generation Constructs. Cancers. 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/cancers16020447.

- Drago, J. Z.; Modi, S.; Chandarlapaty, S. Unlocking the Potential of Antibody–Drug Conjugates for Cancer Therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2021, 18 (6), 327–344. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41571-021-00470-8.

- Almagro, J. C.; Daniels-Wells, T. R.; Perez-Tapia, S. M.; Penichet, M. L. Progress and Challenges in the Design and Clinical Development of Antibodies for Cancer Therapy. Front. Immunol. 2018, Volume 8-2017.

- Wagh, A.; Song, H.; Zeng, M.; Tao, L.; Das, T. K. Challenges and New Frontiers in Analytical Characterization of Antibody-Drug Conjugates. MAbs 2018, 10 (2), 222–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420862.2017.1412025.

- Wu, G.; Gao, Y.; Liu, D.; Tan, X.; Hu, L.; Qiu, Z.; Liu, J.; He, H.; Liu, Y. Study on the Heterogeneity of T-DM1 and the Analysis of the Unconjugated Linker Structure under a Stable Conjugation Process. ACS Omega 2019, 4 (5), 8834–8845. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsomega.9b00430.

- Collados-Ros, A.; Muro, M.; Legaz, I. Gemtuzumab Ozogamicin in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Efficacy, Toxicity, and Resistance Mechanisms—A Systematic Review. Biomedicines. 2024. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines12010208.

- Oostra, D. R.; Macrae, E. R. Role of Trastuzumab Emtansine in the Treatment of HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Targets Ther. 2014, 103–113.

- Li, H.; Li, H. A Narrative Review of the Current Landscape and Future Perspectives of HER2-Targeting Antibody Drug Conjugates for Advanced Breast Cancer. Transl. Breast Cancer Res. 2021, 2.

- Wedam, S.; Fashoyin-Aje, L.; Gao, X.; Bloomquist, E.; Tang, S.; Sridhara, R.; Goldberg, K. B.; King-Kallimanis, B. L.; Theoret, M. R.; Ibrahim, A. FDA Approval Summary: Ado-Trastuzumab Emtansine for the Adjuvant Treatment of HER2-Positive Early Breast Cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020, 26 (16), 4180–4185.

- Matsuda, Y.; Mendelsohn, B. A. An Overview of Process Development for Antibody-Drug Conjugates Produced by Chemical Conjugation Technology. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2021, 21 (7), 963–975.

- Dong, W.; Wang, W.; Cao, C. The Evolution of Antibody‐drug Conjugates: Toward Accurate DAR and Multi‐specificity. ChemMedChem 2024, 19 (17), e202400109.

- Al-Karmalawy, A. A.; Eissa, M. E.; Ashour, N. A.; Yousef, T. A.; Al Khatib, A. O.; Hawas, S. S. Medicinal Chemistry Perspectives on Anticancer Drug Design Based on Clinical Applications (2015–2025). RSC Adv. 2025, 15 (43), 36441–36471. https://doi.org/10.1039/D5RA05472A.

- Conilh, L.; Sadilkova, L.; Viricel, W.; Dumontet, C. Payload Diversification: A Key Step in the Development of Antibody–Drug Conjugates. J. Hematol. Oncol. 2023, 16 (1), 3.

- Tashima, T. Delivery of Drugs into Cancer Cells Using Antibody–Drug Conjugates Based on Receptor-Mediated Endocytosis and the Enhanced Permeability and Retention Effect. Antibodies 2022, 11 (4), 78.

- Frigerio, M.; Camper, N. Linker Design and Impact on ADC Properties. 2021.

- Lei, Y.; Zheng, M.; Chen, P.; Seng Ng, C.; Peng Loh, T.; Liu, H. Linker Design for the Antibody Drug Conjugates: A Comprehensive Review. ChemMedChem 2025, 20 (15), e202500262.

- Su, D.; Zhang, D. Linker Design Impacts Antibody-Drug Conjugate Pharmacokinetics and Efficacy via Modulating the Stability and Payload Release Efficiency. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 687926.

- Lim, Y. J.; Clarissa Lau, P. S.; Low, S. X.; Ng, S. L.; Ong, M. Y.; Pang, H. M.; Lee, Z. Y.; Yow, H. Y.; Hamzah, S. B.; Sellappans, R. How Far Have We Developed Antibody–Drug Conjugate for the Treatment of Cancer? Drugs Drug Candidates 2023, 2 (2), 377–421.

- Debon, A.; Siirola, E.; Snajdrova, R. Enzymatic Bioconjugation: A Perspective from the Pharmaceutical Industry. Jacs Au 2023, 3 (5), 1267–1283.

- Dudchak, R.; Podolak, M.; Holota, S.; Szewczyk-Roszczenko, O.; Roszczenko, P.; Bielawska, A.; Lesyk, R.; Bielawski, K. Click Chemistry in the Synthesis of Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 143, 106982.

- King, T. A.; Walsh, S. J.; Kapun, M.; Wharton, T.; Krajcovicova, S.; Glossop, M. S.; Spring, D. R. Disulfide Re-Bridging Reagents for Single-Payload Antibody-Drug Conjugates. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59 (65), 9868–9871.

- Li, M.; Mei, S.; Yang, Y.; Shen, Y.; Chen, L. Strategies to Mitigate the On-and off-Target Toxicities of Recombinant Immunotoxins: An Antibody Engineering Perspective. Antib. Ther. 2022, 5 (3), 164–176.

- Ralston, S. L.; Li, L.; Lee, D.; Clark, D.; Dropsey, A.; Neff-LaFord, H.; Rana, P.; Weir, L.; Sura, R.; Waterhouse, N. Strategies to Reduce the Use of Non-Human Primates in Development of Oncology ADCs with Cytotoxic Payloads. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2025, 105887.

- Sun, Z.; Gu, M.; Yang, Z.; Shi, L.; Zhao, L.; Zheng, M.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Han, K.; Tang, N. Application of Humanized Mice in the Safety Experiments of Antibody Drugs. Anim. Model. Exp. Med. 2025.

- Beaumont, K.; Pike, A.; Davies, M.; Savoca, A.; Vasalou, C.; Harlfinger, S.; Ramsden, D.; Ferguson, D.; Hariparsad, N.; Jones, O. ADME and DMPK Considerations for the Discovery and Development of Antibody Drug Conjugates (ADCs). Xenobiotica 2022, 52 (8), 770–785.

- Jäger, S.; Wagner, T. R.; Rasche, N.; Kolmar, H.; Hecht, S.; Schröter, C. Generation and Biological Evaluation of Fc Antigen Binding Fragment-Drug Conjugates as a Novel Antibody-Based Format for Targeted Drug Delivery. Bioconjug. Chem. 2021, 32 (8), 1699–1710.

- Dragovich, P. S. Degrader-Antibody Conjugates. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2022, 51 (10), 3886–3897.

- Izzo, D.; Ascione, L.; Guidi, L.; Marsicano, R. M.; Koukoutzeli, C.; Trapani, D.; Curigliano, G. Innovative Payloads for ADCs in Cancer Treatment: Moving beyond the Selective Delivery of Chemotherapy. Ther. Adv. Med. Oncol. 2025, 17, 17588359241309460.

About The Author

Mahmoud K. Al-Ruweidi is a pharmaceutics specialist with expertise in rational drug design, discovery, and delivery. Trained as a biomedical engineer, his research spans formulation science and bioengineering approaches to medicine. He has worked across biochemistry, medical devices, and biomaterials, applying interdisciplinary methods to accelerate therapeutic innovation. Beyond the lab, he is an advocate for improving academic systems to better support young scientists and safeguard research integrity.

Mahmoud K. Al-Ruweidi is a pharmaceutics specialist with expertise in rational drug design, discovery, and delivery. Trained as a biomedical engineer, his research spans formulation science and bioengineering approaches to medicine. He has worked across biochemistry, medical devices, and biomaterials, applying interdisciplinary methods to accelerate therapeutic innovation. Beyond the lab, he is an advocate for improving academic systems to better support young scientists and safeguard research integrity.